By: Kathryn Boonstra

As a research-practice partnership, SSTAR Lab engages with program leaders and practitioners in ways that are quite different from traditional academic researchers. One role we may play, particularly when launching a partnership during the ideation or design stage, is to facilitate the development of a theory of change.

What is a theory of change?

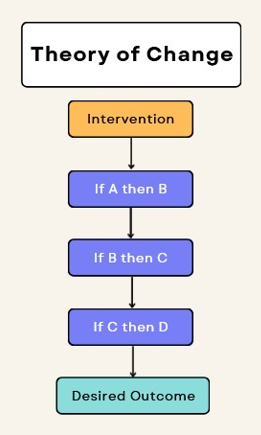

A theory of change describes how a program, initiative, or intervention is expected to bring about certain outcomes. It is a series of ideas that, together, provide a general explanation of how and why we expect the change to occur. It identifies whom the program intends to serve (i.e., priority population), what resources, components, and interventions the program offers (i.e., resources and resulting inputs), how these ingredients are expected to bring about change (i.e., mediators), and why the program exists (i.e., short- and long-term goals). When these ideas are depicted visually, the resulting diagram is called a logic model.

How does a theory of change inform research and evaluation?

For researchers and evaluators, a theory of change provides context for assessing program implementation, measuring impact, and supporting program improvement. It offers guidance to important questions throughout the research process. For example:

- Where and with which populations should we expect to observe impacts?

- What counterfactual conditions would these populations experience absent this program or intervention?

- What resources, activities, or processes need to be investigated to understand the program’s impact?

- What interim information or results will indicate the program is on track to meet its goals?

- What outcomes will we observe and at what level or intensity if the program is successful?

- What data and methods are best suited to measuring these inputs and intended outcomes?

- What theories or related literature are best suited to understanding this program’s context, design, and rationale?

How can practitioners use a theory of change?

For practitioners, a theory of change can function as a compass to help stakeholders make decisions about resources, timelines, or practices, and it can be particularly useful when new information arrives or contexts change. A theory of change also provides a framework for making sense of preliminary or final results, as it documents the desired or intended effects and the mechanisms expected to drive those effects. Finally, a theory of change can be a useful tool for communicating with internal or external stakeholders, such as donors, policymakers, or the media.

How does SSTAR Lab work with partners to develop and document a theory of change?

Facilitating the development of a theory of change is one of the roles SSTAR Lab may play during the planning or ideation phase of a new project. In our experience, practitioner partners often start with ideas—whether latent or explicit—about many components of a theory of change.

One area that is often murky—and where research partners can offer support—relates to the mechanisms that link inputs and intended outcomes. These mechanisms can be thought of as a series of “if/then” statements:

- IF you do these planned activities [Intervention], THEN you will reach these intended populations [A]

- IF you reach these populations [A], THEN you will observe these measurable outputs [B].

- IF you achieve these measurable outputs [B], THEN you will have these short-term results [C].

- IF you achieve these short-term results [C], THEN you will achieve these medium-term goals [D]

- IF you achieve these medium-term goals [D], THEN you will reach this desired outcome.

For example, programs may fall short of reaching their goals if they fall victim to what I call the “know equals do” fallacy, which assumes that once people know better, they do better. However, knowledge alone is rarely sufficient to change behavior, particularly when that behavior confers benefits in other domains. However, knowledge gains can be one link in a larger theory of change, as when information is coupled with resources, access, and/or social supports.

To help surface the links between intervention activities and desired goals, it can be helpful for researchers and practitioners to reflect questions such as:

- What are the missing links from our intervention to our desired outcomes?

- What are the key things that need to be true for our planned activities to lead to our desired outcomes?

- If we assume that our planned activities will lead to our desired outcomes, why do we assume that?

- Who or what do we expect to change after we implement our planned activities? How? (e.g., awareness, skills, values, motivations)?

- What measurable short-term goals would help us know if we are on track to meet our desired outcomes? (e.g., actions, policies, practices, decisions)

- Is more than one mechanism or strategy at play in our intervention?

In our role, Lab researchers might conduct literature reviews, provide empirical evidence, or suggest theoretical frameworks that can substantiate or inform revisions to a theory of change. We can compile what we know about the program into a draft logic model, share with partners, reflect, and revise as needed. Revisions might also be needed when preliminary findings come in, since these may uncover new insights into whether and how the program is working as intended. Ultimately, the theory of change should be a tool that both researchers and practitioners return to, and revise, throughout the life of the evaluation.

The next post in this series will describe how SSTAR Lab worked with stakeholders to define the Teacher Pledge program’s theory of change.